Long Tan – A quest for Honour and Integrity

By David Ellery – Defence Reporter

*This article appeared in The Canberra Times on 15 January 2011 but as there is no online version it has been reproduced here.

The greatest impediment to an honest assessment of the way honours were allocated after the battle of Long Tan is a concept that dates back to Roman times. ”De mortuis nil nisi bonum” effectively translates as ”of the dead, (speak) nothing but good”.

Long Tan is a special challenge in that many of those honoured as well as those denied honours are dead.

There has been an apparent reluctance by some of those charged with making tough calls on these issues to dig too deeply.

Three figures central to this debate are Brigadier Oliver David Jackson DSO OBE, Lieutenant Colonel Colin Townsend DSO and Second Lieutenant Gordon Sharp, a platoon commander with Delta company.

All three are dead. The first two, who were not physically present on the battlefield, received Distinguished Service Orders then second only to the Victoria Cross as an award for gallantry for their ”parts” in the battle. Both lived to ripe old ages.

The third, the junior officer Gordon Sharp, received no honours even though he was one of the first to die in the firefight almost 45 years ago.

Jackson died aged 85 in 2004. He was the commander of the Australian task force in Vietnam on August 18, 1966, when Long Tan was fought.

He graduated from RMC Duntroon in 1939, served with distinction in the Middle East and New Guinea during World War II, saw action in Korea and served as the Australian military attache in Washington in the late 1950s.

At the time he arrived in Vietnam, Jackson was one of Australia’s most respected and experienced commanders.

During the battle he reportedly spent much of the time in his tent, having delegated field command to Townsend.

He has been strongly criticised by the battlefield commanders for failing to disclose intelligence reports indicating the North Vietnamese may have been present in force and for delaying the dispatch of the relief force because he feared a major attack on the base at Nui Dat.

Jackson’s obituary, published in the Australian Army Journal, made only a passing mention of his DSO and did not link it to the action at Long Tan.

This was despite the fact the citation, published in the same edition of the London Gazette as the citation for the Military Medal awarded to Harry Smith for his courage and leadership under fire, reads ”in one action (Long Tan) on August 18, 1966, he personally directed the engagement which accounted for 254 enemy dead by body count with very light comparative losses to his own troops. His able personal direction was a decisive factor”.

Jackson’s subordinate and fellow Long Tan DSO recipient died on June 10, 2006, at the age of 79.

Townsend’s personal courage is unquestioned. He was one of three Australian platoon commanders involved in the relief of an American parachute battalion at the Battle of the Apple Orchard in Korea in October 22, 1950.

During the Battle of Long Tan he made a determined effort to join Harry Smith at Delta company headquarters in the middle of the rubber plantation where the action was fiercest.

But, and it is a big but, by the time he arrived the battle was over and the Vietnamese had withdrawn.

And, significantly, by ordering the armoured personnel carrier-borne relief force to wait for him to catch up he caused its commander, Lieutenant Adrian Roberts, to divide his troop which could have had devastating consequences.

The citation for Townsend’s DSO states: ”As soon as the initial heavy contact with the enemy was made by his company (Delta) on patrol he moved immediately with a relief company in armoured personnel carriers to join his company and took firm and effective control of the battle”.

This, according to Harry Smith and Adrian Roberts, falls far short of the standards of accuracy expected for citations for bravery and makes a mockery of claims by subsequent reviews they had to deny individual awards to men present at the battle in order to preserve the ”integrity” of the honours system.

Commenting on Townsend’s citations, Smith said ”these citations, written by his seniors, could be considered as tantamount to perjury”.

Smith has also consistently questioned the claim in Jackson’s citation the Brigadier ”personally directed” the battle.

”He (Jackson) certainly didn’t give any orders to me,” he said.

There have been subsequent attempts to deflect criticism of Jackson’s and Townsend’s DSOs by claiming they were not for gallantry at Long Tan but for ”overall service”.

Major General Peter Abigail, Major General Steve Gower and Brigadier Gerry Warner, writing in the 2008 Long Tan Recognition Review, state: ”both awards (Jackson’s and Townsend’s DSOs) relate to their entire periods of command”.

That finding, like much that was published under their imprimatur, is open to question.

In 1966 the guidelines for the Distinguished Service Order were clear cut it was for gallant leadership in the field; not to be confused with an award for good service.

That did not change until the mid- 1990s.

Either Townsend and Jackson received their DSOs as a result of their connection with Long Tan or else the awards were made inappropriately there is no middle ground.

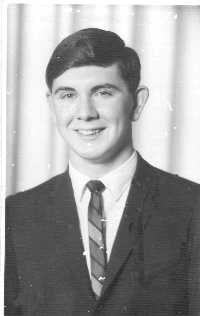

The third player in this account is Second Lieutenant Gordon Sharp, a National Serviceman from Tamworth who had survived the accelerated officer training course at Scheyville and been sent to Vietnam as a platoon commander.

Before being called up he had worked as a television cameraman.

Popular at school, a keen athlete and with an active social life, the 21-year-old should have had his whole life ahead of him.

In the early stages of the battle, aware his platoon was being cut off, Sharp rose to his knees to direct artillery fire and was shot through the neck.

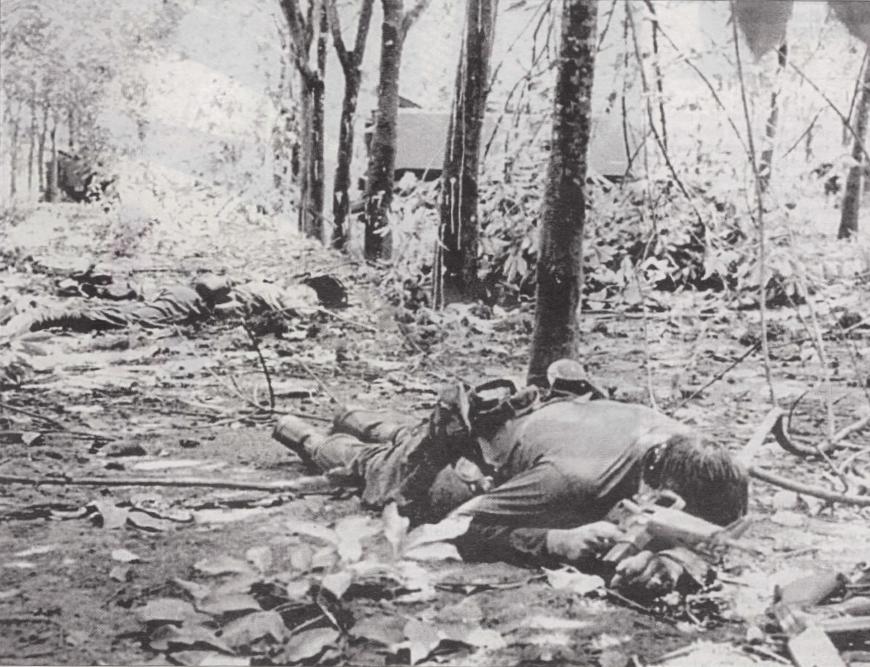

A famous photograph taken the following day shows him dead on the battlefield, his M16 still clutched in his hand.

His Mentioned In Despatches was denied at the same time the same award was made to a postal officer at Vung Tau (a rest and recreation facility near Saigon) for ”good administrative procedures”.

If the cost of appropriately honouring Sharp and the others who were denied the awards they were nominated for is a re-examination of the factual accuracy of the awards to senior officers who weren’t at the battle then so be it.

Until honour is fulfilled on this point the military awards system has no integrity to defend.